Glimpsing the Future Through Torin-Yater Wallace

Standing at the base of Buttermilk Mountain and waiting for freshly-minted Winter X Games 15 Ski Superpipe silver medalist Torin Yater-Wallace to climb the podium is akin to calling for an encore at a Phish show in Burlington, Vermont. After all, Yater-Wallace is a born-and-bred Aspenite (he lives in nearby Basalt, CO), and at age 15 with sponsors like Armada, Smith, and Target, he has already burst onto the freeskiing scene before, well, bursting onto the scene. And yet among all the fans and lookers-on—many around Yater-Wallace’s age, dressed for a night of specatation—there stands a man in an orange jacket and pants, helmet on, boots strapped, and skis in hand, who, like Yater-Wallace, looks as if he just got off the pipe himself.

Read more

“I know Torin gave it his all,” says Aaron Anderson, Yater-Wallace’s first coach at the Aspen Valley Ski Club, “And after he crashed on his first run that was like money in the bank, because to watch Torin crash it’s like, he’s definitely not going to crash again.”

Yater-Wallace is just one of several X Games athletes to come out of the Aspen Valley Ski Club, or the AVSC, a non-profit youth skiing program based at Aspen Highlands which provides over 2,000 kids in the Roaring Fork Valley the opportunity to engage in winter sports. The AVSC offers all levels of instruction and training, from weekend recreation programs to high-level competition development. Following the lead of other locals like skiers Matt Walker and Anne Segal or snowboarder Gretchen Bleiler, Yater-Wallace began his AVSC career at age 7 when, as a budding moguls skier, his mom Stace would take him to once-a-week sessions with the park and pipe team.

“Sure enough, his Mom shows up with this little pee-wee of a kid with the smallest twin tips we’d ever seen,” says Geoff Stump, head coach of AVSC’s freeride team. “It was like, where did you get those twin tips?”

At AVSC, the age cut-off for the older park and pipe team is 12, but by age 11, Yater-Wallace was officially being trained by the squad, which travels to competitions like the Dew Tour and Gatorade Free Flow Tour, and was “hitting the rails and killing it,” in the words of Stump. By age 12, Yater-Wallace was landing switch 540s, 720s, and 900s, and within the next year he stuck his first switch to cork. Now he stands as a Winter X Games medalist, and, some may say, the future of the sport.

“The precedent that Torin has set by example actually facilitates my job quite a bit,” says Anderson, who, like the other coaches, films training sessions for his skiers, many of whom like watching Torin’s videos from around their age as much as their own. “Motivation is always an aspect of training with these kids, and their motivation is that much higher.”

Anderson, who grew up as a racer in the Pennsylvania’s Poconos before heading out west for college and then switching to freestyle in the late 90s, currently coaches the AVSC’s development program, where kids train every weekend at Highlands in addition to a half-day after class two days per week. Aspen High School at the base of Highlands is so close to the mountain’s chairlift that the student-skiers essentially walk out of the classroom and onto the slope.

“Yeah, they’re pretty lucky,” Anderson says.

The AVSC, which also trains at Snowmass, is also currently building an “air-hill” at the base of Aspen complete with airbags, foam pits and trampolines to go along with its summertime water ramps. Stump, who started as the head coach in Aspen in 2002, emphasizes teaching consistent take-offs for well-tested body maneuvers. Amazingly, freeride park and pipe has the lowest injury rate of any discipline at the AVSC (including Nordic skiing) and club-wide, its programs have a far lower injury rate as compared to the national average.

“We have a little bit of a conservative approach in a go-for-it sport to make sure athletes are trying tricks they’re qualified for,” says Stump. “They learn training methods that help you stay in the game as opposed to sitting on the couch, and we try to keep it as much fun as we can—that’s the point.”

In addition to Yater-Wallace, several other AVSC athletes are budding within the program or already breaking onto the pro tour. In February, at the Free Flow Tour Finals at Snowbasin, Utah, 16-year old Aspen local and one of Yater-Wallace’s best friends Alex Ferreira won superpipe to earn an automatic spot at the first stop of next year’s Winter Dew Tour. (Yater-Wallace, who watched Ferreira from the top of the pipe, had just missed the cut-off at the FIS World Championships held in Park City earlier in the month.) Within the AVSC, however, skiers Joey Lang, 12, Gage Car, 13—who according to Stump can do rodeos and mistys with grabs that even Yater-Wallace wasn’t doing at that age—and Kenan McIntyre, 12, are all also on the rise.

“Torin kinda highlights what it is teaching my style and what I think training should be in terms of learning tricks and executing them in contests,” says Anderson. “It’s pretty important for most kids right now in this sport to have a coach.”

And, as the International Olympic Committee considers adding ski superpipe and slopestyle to its events, Stump, who saw the moguls evolution of the '70s and '80s, knows that with the Olympics comes a major shift in the structure of the sport. The FIS will set its regulations, national teams will form and train, and the judging will become more critical.

“The sport will survive and will be guided into the Olympics,” he said. “But like with everything, with more and more regulations, it changes things. The more rules, the more inaccessible it becomes to the kid on the street or who works all winter for his ticket.”

Yet the AVSC—which provides over $600,000 a year in subsidies and scholarships and is entirely donation-driven—emphasizes the character and opportunity given to its athletes as much as their performance.

“With Torin, we’re going to try to keep him grounded with all the hoopla in the next few years,” says Anderson. “The track he’s on is one he’s got to stay on for success and remain humble throughout the whole process. We want to be the front line of innovation with athletes going to the Olympics.”

Yet for Stump, who’s seen the trends in skiing and remains supportive of the Olympic dream, the sport will always, as Dr. Ian Malcolm says in Jurassic Park, find a way.

“Lo and behold, some kids are going to be out in the backcountry and find something to do that’s a whole lot of fun,” he says. “And we’ll be back where we started again.”

This piece was originally published on The Ski Channel on March 8, 2011. This is a revised version.

Shine a Light for a Cause

Last year, Chris Del Bosco lit up Aspen en route to Winter X Games gold in Skier X. This year, he hopes to do the same for a country where snowfall makes world news, and whose last Winter Olympic team featured one cross-country skier.

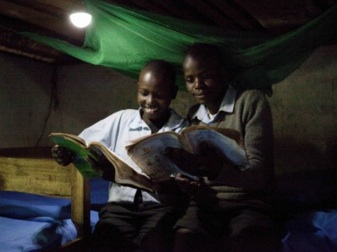

By partnering with the Denver-born company Nokero, who make the world’s only solar powered light bulb, Del Bosco has found not only a sponsor but also an ally in charity. Nokero—which is short for “No Kerosene,” as in the polluting substance often burnt for light by those without electricity—has teamed up with the defending Skier X gold medalist in a program called Ski 4 Light, where Del Bosco aims to raise $20,000 in donations and thus deliver 1,000 solar-powered bulbs to Kenya.

Read more

“I wanted to find something worthwhile,” said Del Bosco by phone as he drove to Aspen on Wednesday for ESPN Winter X Games 15, which run from January 27-30. “And this was a perfect fit for me, I was looking for something to add a little bit of meaning to my skiing.”

In addition to donations, Del Bosco and Nokero have pledged an additional 1,000 bulbs if he can successfully defend his title. And as if to remind the world of their project, Del Bosco’s helmet will feature a solar panel and battery powered-LED with the word “Nokero” emblazoned across the front, he says, “like a sticker.” Del Bosco will also travel to Kenya in July to bring the bulbs as part of the Bold Leaders exchange program, where American children visit Kenya while Kenyans come to explore the outdoors in the US in an effort to improve relations between the two countries—one bountifully electrified and the other were many still use kerosene lamps.

“We never really think about it,” said Del Bosco. “We turn on a light switch and we have lights and a lot of these people live off the grid.”

Nokero’s solar-powered bulb inventor Stephen Katsaros, a friend of Del Bosco’s from back when they were both living in Vail, said that although the company was originally skeptical of the partnership, when the charity side came up, things began moving quickly.

“Chris is just a wonderful person, I think that we came up with this really sweet idea,” Katsaros said.

That idea (the helmet) was then hatched on the first day of the new year, four days later engineers began building the model and after two prototypes it’s ready—like Del Bosco—to go at X. Indeed, as if on top of Del Bosco’s long road to the sport—he was kicked off the US Alpine team at age 17 for a positive marijuana test and in 2006 made a last-chance qualifier to Winter X where he went on to win the bronze—Del Bosco also had surgery last May after the Vancouver Winter Olympics on a 35% tear in the patella tendon of his left knee. He considered scrapping this season entirely, but after a strong rehabilitation in the fall currently sits at second in the World Cup standings and is ready for the main event in Aspen.

“It’s a big one, one I always look forward to racing,” he said. “This year I stepped it up and hopefully it’ll carry on through.”

Added Katsaros, “he went down the wrong path at one point, but he is where he is today because of hard work and stick-to-it-ness. He’s a great guy and he’s determined. He works so hard, he embodies a lot of the traits that I respect.”

And, to emphasize the goal of Ski 4 Life, Katsaros notes that 1.6 billion people in the world live without electricity.

“How incomprehensible is that for the average Westerner?” he asks.

About as incomprehensible as a September snowstorm in Kenya.

To donate to Ski 4 Light, visit chrisdelbosco.com or nokero.com. Photos courtesy of nokero.com.

This article originally appeared on The Ski Channel on January 28, 2011. This is a revised version.

Racing Up Jackson Hole—It Is What It Sounds Like

Sometimes hindsight exists on the finish line. At the bottom of Jackson Hole’s tram line, at the end of the 2011 US Ski Mountaineering Championships, Mark Smiley looked at his wife.

“I knew when you started out,” he said, “it was like, ‘She’s having a good day.’”

Read more

Janelle Smiley gave a laugh that summed up the race. “It started out nice,” said the 29-year old from Crested Butte, “and got worse.”

Indeed, with a cloudy and warm morning at 6,000 feet morphing into a gale at 10,000 feet, Saturday’s field of 90 racers—divided into “race” (ultra-light setups for skinning and bootpacking up Jackson’s legendary pitches), “heavy metal” (backcountry gear running the race course), “recreation” (a separate course on any gear) and 2-person relay (the race course on any gear)—surely felt the spectrum of Teton winter weather. Still, considering last year’s race was in March, the colder, wilder weather and better snow were not the only changes brought on by the shift to January.

“It brought more people here,” said Pete Swenson, director of the US Ski Mountaineering Association. “We wanted to make it that if you’re national champion it’s the middle of the winter. It makes it more relevant.”

And international. Reiner Thoni, 26, who won the men’s race division on a course that features bootpacks up both the headwall above Jackson’s gondola as well as up Corbet’s couloir, hails from Belmont, British Columbia. He trains on logging roads in his native Canada but in between makes sure to get all the fresh snow he can.

“On your low-intensity days,” he said at the base after covering the 8,000 vertical-foot course—one that might as well be called Jackson’s Greatest Hits—in a blistering 2:39.14, “you gotta keep yourself happy.”

Brandon French, from Kalispell, MT, finished just behind Thoni in a time of 2:40.04.

“We had a pretty big group to start and it just slowly dwindled and then by the finish it dropped down to about five,” said the newly-crowned 30-year old US national champion (Thoni’s Canadian, recall). “The wind at the summit was the toughest part. It was just cold on the face, the fingers were frozen.”

In fact, with the wind chill at the summit well below zero, several competitors were advised to cover up bare skin against frostbite. That same wind also visibly wind-loaded the cornice above Corbet’s in slow motion, but it didn’t change Smiley’s take.

“Those bootpack couloir things were super fun,” she said “Totally into those.” Smiley finished in 3:07.21 with second-place racer Sari Anderson from Carbondale, CO coming in at 3:08.45.

“Sari and I were just tagging it back and forth,” she said. “I’d pass her and she’d pass me. Finally there at the end I guess I took it. She was awesome. I stuck on her tail and hoped I’d get second. The last little skin was kinda a kick in the pants.”

At the awards ceremony, with well-earned pizza and beer fueling the post-race, Swenson made it clear this event was essentially the big bang for the newborn USSMA, which sells licenses and provides race insurance for competitions around the country.

“And we’d like to bring back the national series and maybe invite some Canadians; go up there if they stop beating us,” he joked.

As for Saturday, however, where the top three American men and women automatically qualify to go to worlds, Swenson could already see the future.

"This is the most competitive race we’ve ever had in North America, and getting more people at the event, its really rewarding,” he said. “Yeah, it was pretty junky, everyone was totally blown over. But it was awesome too.”

This piece was originally published on The Ski Channel on January 10, 2011. This is a revised version.

Sugarloaf Tests Emergency Response Procedures

The call came at 9:18 a.m. on November 7 in Maine’s Carrabassett Valley, without a foot of snow in sight. “We’ve got a derailed Sawduster and Snubber,” said a voice on Sugarloaf’s Ski Patrol radio. “Signal 1000, all stations, signal 1000.”

Read more

Two hundred yards downhill from the base lodge, close to 30 people were strewn on the ground, beneath the point where the two chairlifts cross. A cacophony of cries split the grey November air and Ski Patrol moved quickly to assess the scene. Others who were not injured offered to help, often holding patients’ heads while trying not to lose their own.

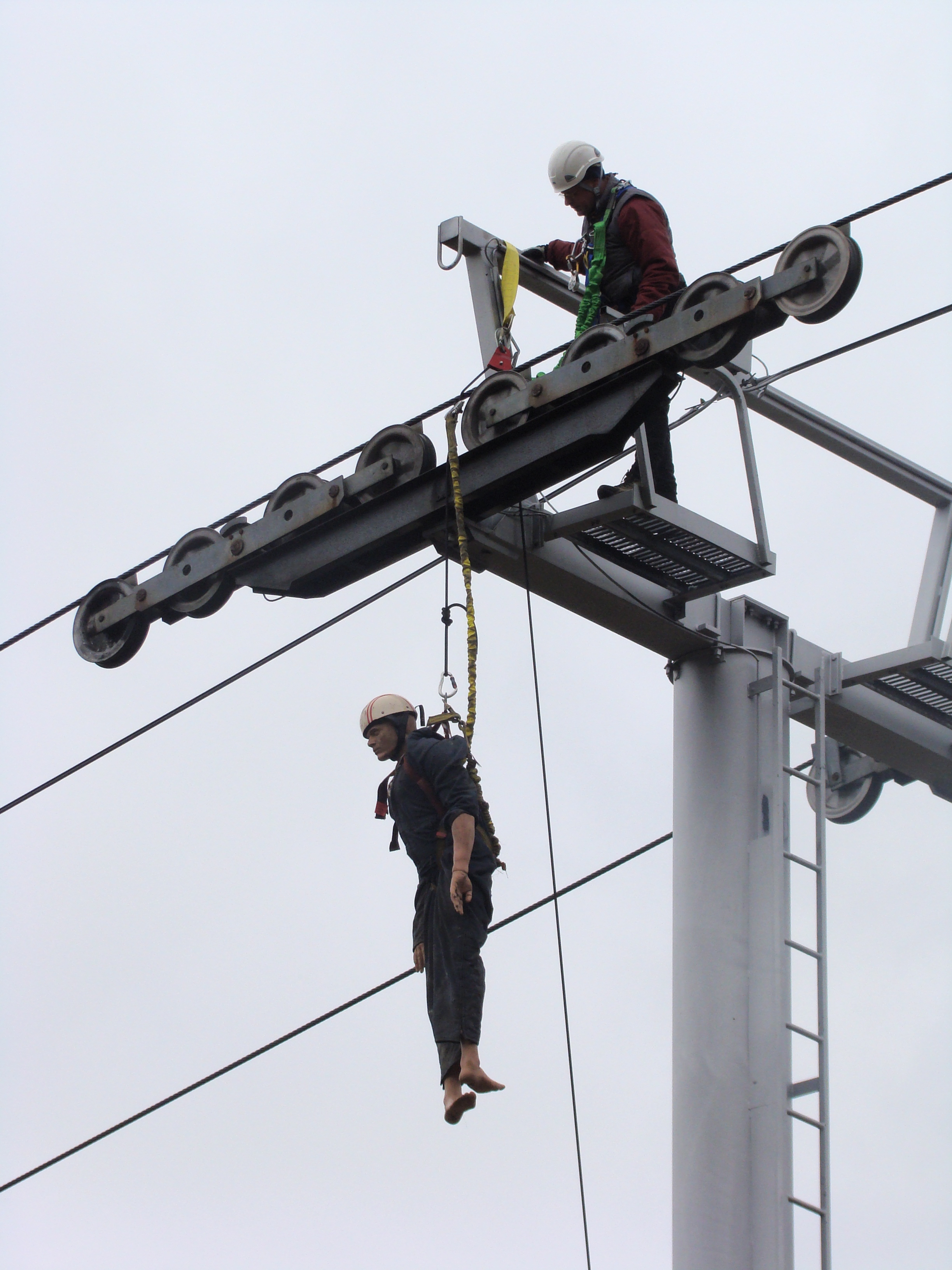

“That guy has blood coming out of his head!” a man yelled. “That guy’s unconscious!” To his left, a woman sat with red liquid covering her leg. Uphill, some victims were already being tagged for bodybags. And above, dangling in the air from one of Snubber’s towers, like a worm barely hanging on a hook, was the figure of a mountain maintenance worker who was knocked off the lift when Sawduster derailed and came crashing down. “53 to 4 do you copy?” came a voice on the radio. “We’ve got a man hanging from 19.”

In actuality, the man of tower 19 would be real. But on this day, he was a dummy, and Sugarloaf was merely testing its emergency response procedure. The mock was hatched in October 2009 at one of the mountain’s tabletop drills, where ski patrol and emergency workers discuss how they would handle such situations should they actually occur.

“But we recognized that this county and this area has a tremendous amount of services,” said Earl Warren of Sugarloaf Ski Patrol, who spearheaded the drill, “so when we tested at the table top, we wondered aloud, saying, ‘Could we do that full scale?’”

And indeed, after the initial call of 19 casualties went out, the services poured in. At 9:40, fire trucks and ambulances arrived, soon joined by Eustis first responders from Kingfield and Rangely and Northstar-EMS. Tri-county medical services had a triage center set up by 10:00, and as the morning turned to midday, patients of the highest priority were shuttled to Franklin Memorial Hospital in Farmington, 40 minutes away. This tiered response then continued “downstream” with “mirror” patients already stationed in Farmington, allowing the staff at Franklin Memorial to determine for themselves who they needed to send out for further treatment.

Emergency prep 101.

“The idea of this exercise is not just to test Sugarloaf but to see how everyone would respond to a situation like this,” said Ethan Austin, Sugarloaf’s Communications Manager. “And this was intentionally made much larger than any incident we would expect. It’s good to prepare for it.”

Sugarloaf even left a few ambulances and intentionally did not call Maine’s LifeFlight helicopter to allow for the possibility of any real-life emergencies arising during the drill, and sure enough, NorthStar used the LifeFlight chopper on a call—one that all mock responders heard on their radios. “’Cause if this were really happening,” said Austin, “the rest of the world wouldn’t stop.”

On the mountain, those in chairlifts downloaded via either fire truck bucket or rope harness, and the drill finished at around 11 a.m., two hours earlier than expected. Back inside the base lodge, volunteer participants warmed up while emergency responders debriefed. Delinda Smith of the Sugarloaf Ski Club was the last one off Sawduster. “It was cold,“ she said. “But it was fun.” Joked her husband Peter, “I volunteered her.”

At the debriefing, responders noted room for improvement—pieces of advice such as moving beyond the everyday response system by using other radio stations—but the general consensus was of a successful drill. “A good sized-city wouldn’t be able to provide this many EMS-trained personnel,” noted John Tobias of Carrabassett Valley Fire. Added Austin, “I was at the command post, and you could just hear the calls coming in.”

Still, as both Warren and Austin noted, this was only a drill. “In designing this, we very quickly realized how far-reaching it would go,” said Warren. “And it’s impossible for something like this to go exactly as planned.”

"So, beers at The Rack?"

And in addition to volunteers, responders, and Ski Patrol—257 participants in all—both the Maine Emergency management Association and the National Ski Patrol observed to provide their own feedback should something happen like the downloading of Sugarloaf’s Superquad. “And that,” noted Austin, “would take a lot longer because it’s a bigger, longer lift with a lot of tricky terrain underneath.”

But MEMA’s presence was also educational, as it was, in essence, for all. “The lessons we learned today can be applied to a number of different scenarios,” said Warren, “it doesn’t have to be a ski area.”