Trail racing

A great way to mix it up

For our regular cross country runners out there—those athletes training to race on three-plus miles of gravel and dirt—the rise of trail running is something of a “told-you-so” moment in running. Training on trails is fun? Told you so. Planning out a race schedule where the courses are varied each week is fun? Told you so. Logging miles and scenic vistas is fun? Told you…well, that is where trail running is unique. What follows is a first-person look at the fastest-growing sport in the United States, one that had 6 million Americans racing in 2012 after 4.8 million participated in 2009—and one where racing up mountains is no hyperbole.

Read more

Firstly, why the appeal? Well, for as much as road racing (the other common series for many post-collegiate cross country runners, and Marx’s own Team Run) has its Grand Prix and local striders and pub runs, trail racing has its Mountain Circuit and weekend warriors and festival atmosphere. The Western NH Trail Run Series (WNHTRS), a group of nine different trail events occurring in the upper valley of New Hampshire and Vermont each summer, is one of several series in New England, the others being the North Shore Trail Series, South Shore Trail Series, Grand Tree Trail Series and, of course, USATF New England Mountain Circuit. (Tragically the founder of the WNHTRS, Chad Denning, passed away while hiking a section of the AT this past summer; the final race of that series, Lost a Lot, was run in his memory.) Trail running courses typically follow tight single-track, such as on old Mount Ascutney Ski Area’s mountain bike trails during WNHTRS’s “Frenzy in the Forest,” and often feature several calf-cramping ascents followed by quad-burning downhill sections into the finish. Indeed, it is precisely these elements that blur the line between cross country running and “fastpacking,” making for a unique racing challenge.

That’s not to say that trail running is its own bubble, however. Sure, there are those athletes who exclusively pencil in events like the Mountain Circuit and WNTRS on their race calendars, but more often the field is a meeting point for a variety of athletes; road runners from running clubs looking to mix up their season, high school Nordic athletes looking to improve their fitness before the winter, or veteran runners just having fun on the trails. This summer, while racing the WNTRS, it was not uncommon for the field to spread out to a 45-minute gap between the leaders and last finishers, with the leaders cheering the latter on to the finish line. And with course distances ranging between five miles and just under eight miles, a series like WNHTRS is feasible to race without half-marathon or marathon level of training.

So, all in all, if you have yet to try a trail race, time to mix it up. And get ready for some real hills!

This piece was originally published on Marx Running & Fitness's blog on October 24, 2014.

The following two pieces were written as "mock" articles in the spirit of my 2011 Thomas J. Watson Fellowship application. I was a Finalist for the Fellowship — my project was essentially to answer the question: what actually works in the sports-as-diplomacy metaphor?

Beisel back to China

Heading back to China for World Championships, Beisel happier than ever

Sometimes, even when you’re staring at the bottom of a pool, a change of scenery still makes waves. For Saunderstown-born Elizabeth Beisel, 18, a member of the US Women’s Swimming and Diving Team, such change has meant an up-shift of gears.

Read more

Indeed Beisel, a 2010 graduate of North Kingston High School who is currently competing at the FINA World Championships in Shanghai through July 31, recently completed her first year of school as a Gator at the University of Florida, where the already-energetic Rhode Islander injected even more life into her swimming career.

“Working with a different group of people like I’ve had in the first year of college has refreshed the way I look at the sport,” wrote Beisel via email as she traveled with the US team on her way to Shanghai. “And I’m starting to like [swimming] a lot more than I did a few years ago just because of the change.”

Beisel, who will compete in the 200-meter backstroke and 400-meter individual medley events to be held Friday through Sunday in Shanghai, swims at Florida under the direction of coach Gregg Troy, who has won 26 national titles during his time in Gainesville and will coach the US Men’s team at the London Olympics next August.

Troy, who has seen his fair-share of Gators-turned world-class swimmers—such as Beijing Olympic medalists Dara Torres and Ryan Lochte—can attest that Beisel’s reformed passion has already shown itself in the practice pool. (Beisel also competed at the Beijing games in 2008, though after posting the best time in the 400 IM prelims did not medal in the final.)

“She has taken her enjoyment of the sport to a new level,” wrote Troy via email. “The energy she brings to practice has created a very likable situation [and] the result has been a greater consistency in training.”

Yet for Beisel, this weekend in Shanghai will be the test to see if practicing consistently translates to sustained top results in pool competition. In the buildup to FINA, for instance, the University of Florida hosted the Southeastern Conference Swimming and Diving Championships in late February, where Beisel won the two events she will swim in China—and notably set an SEC record in the 400-yard IM in the process.

However, in the NCAA Championship meet a month later in Minneapolis, the SEC Freshman of the Year and soon-to-be All-American placed second and third in her two trademark events, the 400IM and 200 back, respectively. Still—and especially for an athlete who trained through sectionals and has only recently begun her seasonal tapering—mental toughness may very well take the day this weekend.

“Coach Troy drills into our heads that we need to be confident when we swim, no matter what,” wrote Beisel. “All you can do is depend on your mental capacity and how confident you are and that’s been a new mentality I’ve had in the last year that’s helped me improve a lot, especially going from club swimming to college swimming.”

Added Troy, “[We have a] training environment with a large group of very experienced athletes who focus on competition at the highest level, [combined with the] ability for us to consistently train at a level that is very intense.”

Indeed, since Troy is the Olympic men’s coach—which requires additional focus on long-course training and competition—Gainesville is more than your typical college pool and attracts swimmers, like Beisel, with international goals on the mind. And yet as Troy emphasized, Florida even goes so far as to make it a priority, gaining ample support from both administration and staff, such as from associate head coaches Martyn Wilby (1982-1986 British National Team member) and Anthony Nesty, a UF alum who won the first-ever Olympic medal for his home country of Suriname in the 1988 Seoul Games—and a gold at that.

“This allows us the ability to work with the athletes in a variety of different styles,” wrote Troy. “Our athletes like Elizabeth who have the opportunity to do something special at the international level will have even more training and racing opportunities than usual.”

And so for Beisel, who noted that she still misses home, where “everyone knows everybody,” she’s at the same time gaining a new sense of place, and one on a global scale.

“It’s going to be really exciting to see all of the other swimmers,” she wrote, “especially since the whole group didn’t taper together. We’re always going to be representing the University of Florida as well as our nations and we’re a really close-knit group. I can’t wait to see how they swim at Worlds.”

This article was originally published in The Standard Times on July 28, 2011. Photo courtesy of Mike Comer/Pro Swim Visuals.

McInerney medals

Westford resident medals at World Summer Games

In the world of horses, life is nonbverbal. Yet for David McInerney, 15, of Westford, that’s just the way life’s magic should be. McInerney, a tenth-grader at Westford Academy who is high-functioning autistic, returned home last Wednesday after competing as an equestrian rider at the Special Olympics World Summer Games in Athens, Greece, where he won two silver medals and a bronze—and in the process displayed mastery of a sport in which verbal communication is rare.

Read more

“We kept saying that he needed to learn to say ‘walk, trot, and whoa’ in Greek,” said his mother Marcy, who traveled to Athens along with seven other family members to cheer on her son, “and I kept teasing him that the horses in Greece had wings.”

To which David replied: “I never used verbal commands, only physical…and of course a Pegasus doesn’t exist.” (A Pegasus is a white-winged horse in Greek mythology symbolizing wisdom and fame.)

Indeed, in many equestrian competitions, riders are forbidden from using verbal commands with their horses, yet that didn’t stop McInerney, whose formal diagnosis is PDD-NOS (pervasive development disorder, not otherwise specified, a condition that affects socialization and communication), from improving his own social skills or hearing the multilayered voices unique to the World Summer Games. In equitation, for example, where riders are judged on their posture while mounted, all seven coaches in the ring would translate the given English instructions into their riders’ respective language at the exact same time. Yet for McInerney, who had won several gold medals at the state finals and for whom this was his first international competition, the cacophony still didn’t deter him from securing a bronze medal.

“The state finals are at a local barn, and you know everyone who’s there,” said his coach Margaret McDaniel. “At the worlds, it’s different riders, different countries, different riding styles—sometimes a matter of hands and feet and leg positions.”

McDaniel, an instructor at Anidmar Stables in Billerica, first hatched the idea of McInerney competing at the World Games last summer. Then, after he was selected for Athens, the instructor traveled with her protégée to Team USA’s training camp in San Diego at the end of March, where, between many games of Uno, McInerney finally got to meet his fellow teammates, coaches, and ride a variety of different horses.

“He had to be prepared to accept others,” said McDaniel. [Before San Diego] “I had him ride with my own personal instructor, with different horses. And his personality has come out more and more, especially since he decided to do the World Games.”

Indeed, six years ago, at his first lesson, McInerney rode a horse named Poop while three instructors surrounded him on the horse, aiding his balance. Then, in Athens last month, McInerney rode a Greek horse named Cool Water, fitting for the self-collection it takes to ride and compete.

“I tested him and he was pretty good for me,” said McInerney, “and I was like, ‘I’ll keep this piece for this game of chess.”

“Riding has given him a lot of confidence,” added Marcy.

The McInerney family’s experience in Greece was more than just athletic, however, as their credentials gave them free admission to many sites and museums. And prior to the Games, which ran from June 25 to July 4, each country’s athletes went to a different part of Greece for team building, as well as to acclimate to the climate and the culture. (Team USA spent five days on the Isle of Rhodes, and Marcy noted that while in Athens the athletes were kept well away from any riots, although strikes on the metro made for a steep taxi bill.)

“And it was very interesting to run into other people with credentials and kind of say we’re here for the same reason,” she said.

Added his sister Patty McInerney, “and even if you couldn’t verbally communicate, you’d give them a thumb’s up.”

So now, back in Westford, David McInerney and the family are reflecting on the experience and already excited about the future. McDaniel, who had David cantering for the first time this year, hopes to have him jumping soon, she said. It’s a long way to come from sitting wobbly atop Poop.

“A lot of times on our way to horseback riding, he will fall asleep on the way there,” said Marcy. “And then he will have his lesson, and he will not stop talking on the ride home. It’s like he gets wired.”

Added David, “I have no idea how that’s even possible; it might happen like magic.”

This piece was originally published in the Westford Eagle on July 14, 2011. All photos courtesy of Marcy McInernery

The following piece was written for and published on the 5Point Film Festival's blog.

The Freedom Chair

You'll often hear in skiing that this sport, this sport where we strap planks to our feet, propel ourselves with sticks in our hands, and arc our way down snow-covered mountains, gives us freedom. You also might hear in skiing that this freedom is powerful like nothing else. Indeed, in this sport where mountains and snow and motion collide, you'll hear that skiing is, simply, like nothing else.

Read more

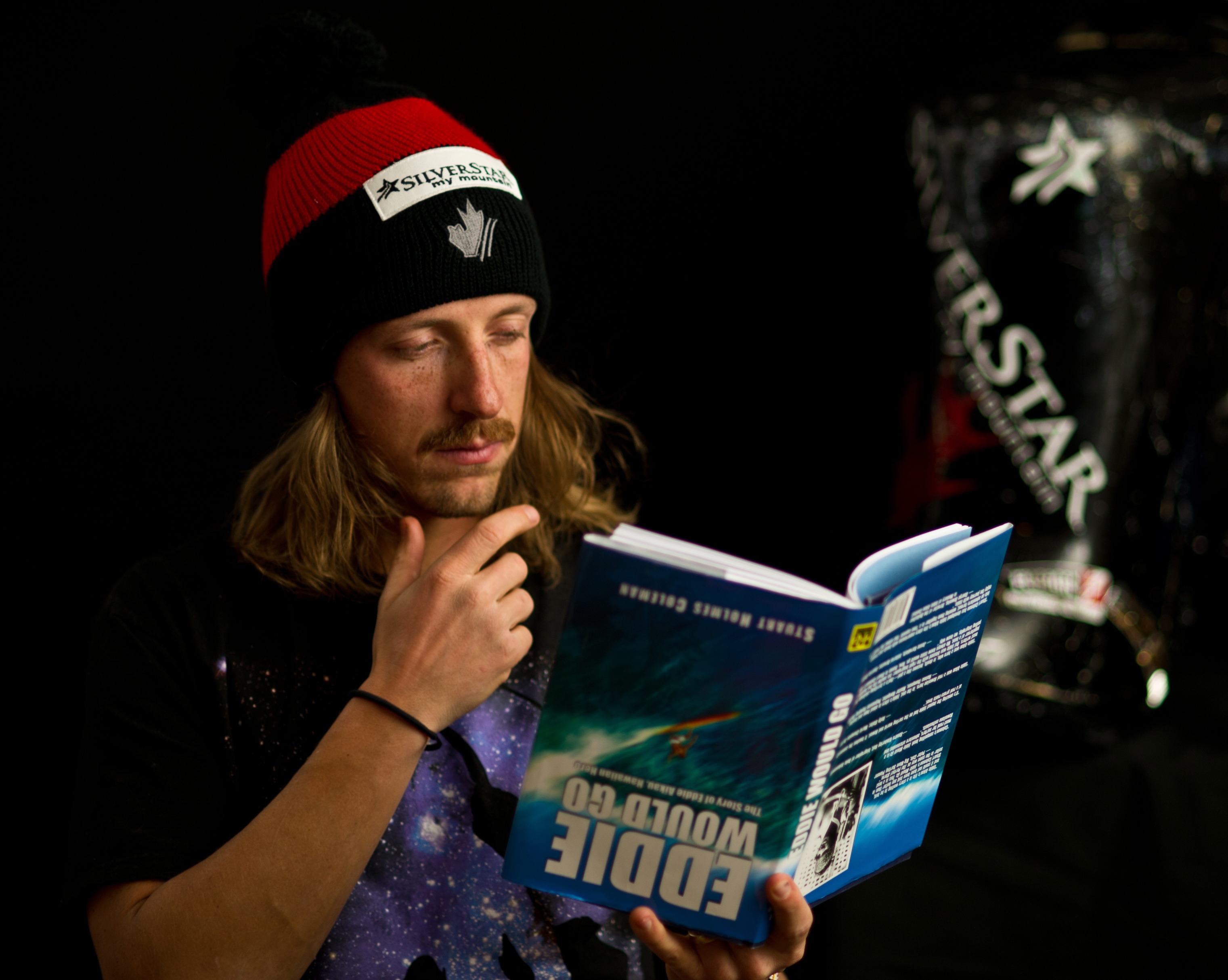

Josh Dueck, star of Switchback Productions' The Freedom Chair, knows all of this, and then some. As a former head coach of the Silver Star Freestyle Ski Club in Vernon, B.C., he experienced it all first-hand. His students, skiers like T.J. Schiller, Josh Bibby, Riley Leboe, and Justin Dorey, are now sewn into freeskiings past and present, a tapestry of cold mornings, switch takeoffs, and smooth landings.

In 2004, Dueck was training for the Canadian Junior Nationals Team when the then-23-year-old overshot a jump and fell 100 feet to earth, dislocating his back and severing his spinal cord. He lost all feeling below his waist. Eight years later, Dueck is a Paralympic silver medalist, an X Games mono skier X gold medalist, and has landed the first backflip on a sit-ski. Credit the power of skiing.

“Keeping my head up and looking forward to the sport of sit skiing [after my accident] gave me hope,” said Dueck. “[And now I'm continuing to share my journey with as many people as possible and be actively involved with those who have encountered challenges in their life and need help along the way.”

The learning curve to get to where he is today was steep, but Dueck is a skier. Imagine having to relearn your balance points for something that was as second nature as walking, but, then again, imagine having been a seasoned competitive freestyler. Imagine having to adjust your equipment continuously, but, then again, imagine having the support of thousands of other paraplegics.

“I was amazed at how everything I knew about skiing before my accident came back,” said Dueck. “It takes a village to raise a child, and a community to raise an athlete.”

Dueck's community came out in full force at the 2010 Vancouver Winter Paralympic Games, and it's only grown from there. Before the Games, Dueck and his wife, Lacey, sold Go Josh Go t-shirts as a travel fundraising effort. The byproduct of the t-shirt campaign was how it united his community of friends and family. Looking into the crowd from the course, Dueck saw his friends from all corners of the world, and all were there to cheer him on.

“It was really cool, there was this motley crew,” he said. “And for the first time I was like, Man, I don't know if I want to compete, I kind of want to be in the crowd, that looks like fun.”

And now, after competing on the World Cup circuit for a number of years as well, Dueck's backcountry prowess, showcased in the film, is beginning to shine. He's interested in creating ways to expand his own access, be it through transport and equipment, and already has a few ideas, such as using snowshoes on his outriggers when crossing level terrain or ski-joring to go uphill.

“The exploration is really interesting for me right now,” said Dueck. “I'm easy to please in the backcountry. It doesn't take much for me to be submerged in overhead blower pow. There could be a foot of fresh and I'll have an epic day.”

Go would Eddie. Go Josh Go. (Josh Dueck)

And so, as he draws up improvements to sit-ski technology for paraplegics like himself, ideally fitting oneself to the chair and ski so that one gets seamless response with each turn, he is also riding skiing's power, the one that never really leaves a skier, even when you've lost then movement in your legs.

“Before, [skiing] was a way to express myself, but now, with reduced motion in the rest of my body, I can't even put into words what it gives me,” he said. “[Still, what] I didn't foresee in the sit-ski before I started was how challenging it was going to be to connect the body to the machine. If I can do that, it's going to open up doors for a lot of people. It'll be like the twin-tip ski.”

For now, though, he'll share his story on the big screen, inspiring others who seek the freedom chair.

“We all face these things and we can all overcome them,” Dueck said. “This film is the product of a couple of things: the love and support of my wife as she encourages me to live my dreams and the vision of Mike Douglas of Switchback Entertainment. In my opinion he's done a phenomenal job of telling my story.”

The Freedom Chair, a film by SalomonFreeskiTV will screen during Friday's evening program. To learn more about Josh Dueck visit joshdueck.com

This piece was originally published on April 26, 2012. This is a revised version.

The following piece was written for and published by Blood, Sweat, and Cheers, which is now a part of Greatist.

Beer Mile World Championships

Beer and running go together like dinosaurs and extinction, Game of Thrones and decapitation and BuzzFeed quizzes and irrelevancy.

But usually the beer comes after the run.

This fall, however, competitors from around the world will drink four beer during a timed mile around the track.

Read more

Alerting college track teams everywhere, it’s the Beer Mile World Championships.

Scheduled for this fall in Austin, TX, the Beer Mile World Championship will level the playing—and drinking!—field between various beer milers competing on different tracks, with different beer, in different conditions throughout the past 20 years.

Pitting the best against the best, current world record holder James Nielsen—who videotaped himself running a blistering 4:57 beer mile in April—as well as 800-meter silver medalist Nick Symmonds will compete.

We're not sure which beer will be served, but our bet is the one most records on BeerMile.com have been set with: Budweiser.

And we'll cheers to that (and not puking). Beer Mile World Championships, Austin, TX; Learn more.

This piece was originally published in Blood, Sweat, and Cheers, which provides daily email services for discovering fun stuff to do with friends, on May 22, 2014. BSC is now a part of Greatist. This is a revised version

The following three pieces were written for and published by The Ski Channel.

Glimpsing the Future Through Torin-Yater Wallace

Standing at the base of Buttermilk Mountain and waiting for freshly-minted Winter X Games 15 Ski Superpipe silver medalist Torin Yater-Wallace to climb the podium is akin to calling for an encore at a Phish show in Burlington, Vermont. After all, Yater-Wallace is a born-and-bred Aspenite (he lives in nearby Basalt, CO), and at age 15 with sponsors like Armada, Smith, and Target, he has already burst onto the freeskiing scene before, well, bursting onto the scene. And yet among all the fans and lookers-on—many around Yater-Wallace’s age, dressed for a night of specatation—there stands a man in an orange jacket and pants, helmet on, boots strapped, and skis in hand, who, like Yater-Wallace, looks as if he just got off the pipe himself.

Read more

“I know Torin gave it his all,” says Aaron Anderson, Yater-Wallace’s first coach at the Aspen Valley Ski Club, “And after he crashed on his first run that was like money in the bank, because to watch Torin crash it’s like, he’s definitely not going to crash again.”

Yater-Wallace is just one of several X Games athletes to come out of the Aspen Valley Ski Club, or the AVSC, a non-profit youth skiing program based at Aspen Highlands which provides over 2,000 kids in the Roaring Fork Valley the opportunity to engage in winter sports. The AVSC offers all levels of instruction and training, from weekend recreation programs to high-level competition development. Following the lead of other locals like skiers Matt Walker and Anne Segal or snowboarder Gretchen Bleiler, Yater-Wallace began his AVSC career at age 7 when, as a budding moguls skier, his mom Stace would take him to once-a-week sessions with the park and pipe team.

“Sure enough, his Mom shows up with this little pee-wee of a kid with the smallest twin tips we’d ever seen,” says Geoff Stump, head coach of AVSC’s freeride team. “It was like, where did you get those twin tips?”

At AVSC, the age cut-off for the older park and pipe team is 12, but by age 11, Yater-Wallace was officially being trained by the squad, which travels to competitions like the Dew Tour and Gatorade Free Flow Tour, and was “hitting the rails and killing it,” in the words of Stump. By age 12, Yater-Wallace was landing switch 540s, 720s, and 900s, and within the next year he stuck his first switch to cork. Now he stands as a Winter X Games medalist, and, some may say, the future of the sport.

“The precedent that Torin has set by example actually facilitates my job quite a bit,” says Anderson, who, like the other coaches, films training sessions for his skiers, many of whom like watching Torin’s videos from around their age as much as their own. “Motivation is always an aspect of training with these kids, and their motivation is that much higher.”

Anderson, who grew up as a racer in the Pennsylvania’s Poconos before heading out west for college and then switching to freestyle in the late 90s, currently coaches the AVSC’s development program, where kids train every weekend at Highlands in addition to a half-day after class two days per week. Aspen High School at the base of Highlands is so close to the mountain’s chairlift that the student-skiers essentially walk out of the classroom and onto the slope.

“Yeah, they’re pretty lucky,” Anderson says.

The AVSC, which also trains at Snowmass, is also currently building an “air-hill” at the base of Aspen complete with airbags, foam pits and trampolines to go along with its summertime water ramps. Stump, who started as the head coach in Aspen in 2002, emphasizes teaching consistent take-offs for well-tested body maneuvers. Amazingly, freeride park and pipe has the lowest injury rate of any discipline at the AVSC (including Nordic skiing) and club-wide, its programs have a far lower injury rate as compared to the national average.

“We have a little bit of a conservative approach in a go-for-it sport to make sure athletes are trying tricks they’re qualified for,” says Stump. “They learn training methods that help you stay in the game as opposed to sitting on the couch, and we try to keep it as much fun as we can—that’s the point.”

In addition to Yater-Wallace, several other AVSC athletes are budding within the program or already breaking onto the pro tour. In February, at the Free Flow Tour Finals at Snowbasin, Utah, 16-year old Aspen local and one of Yater-Wallace’s best friends Alex Ferreira won superpipe to earn an automatic spot at the first stop of next year’s Winter Dew Tour. (Yater-Wallace, who watched Ferreira from the top of the pipe, had just missed the cut-off at the FIS World Championships held in Park City earlier in the month.) Within the AVSC, however, skiers Joey Lang, 12, Gage Car, 13—who according to Stump can do rodeos and mistys with grabs that even Yater-Wallace wasn’t doing at that age—and Kenan McIntyre, 12, are all also on the rise.

“Torin kinda highlights what it is teaching my style and what I think training should be in terms of learning tricks and executing them in contests,” says Anderson. “It’s pretty important for most kids right now in this sport to have a coach.”

And, as the International Olympic Committee considers adding ski superpipe and slopestyle to its events, Stump, who saw the moguls evolution of the '70s and '80s, knows that with the Olympics comes a major shift in the structure of the sport. The FIS will set its regulations, national teams will form and train, and the judging will become more critical.

“The sport will survive and will be guided into the Olympics,” he said. “But like with everything, with more and more regulations, it changes things. The more rules, the more inaccessible it becomes to the kid on the street or who works all winter for his ticket.”

Yet the AVSC—which provides over $600,000 a year in subsidies and scholarships and is entirely donation-driven—emphasizes the character and opportunity given to its athletes as much as their performance.

“With Torin, we’re going to try to keep him grounded with all the hoopla in the next few years,” says Anderson. “The track he’s on is one he’s got to stay on for success and remain humble throughout the whole process. We want to be the front line of innovation with athletes going to the Olympics.”

Yet for Stump, who’s seen the trends in skiing and remains supportive of the Olympic dream, the sport will always, as Dr. Ian Malcolm says in Jurassic Park, find a way.

“Lo and behold, some kids are going to be out in the backcountry and find something to do that’s a whole lot of fun,” he says. “And we’ll be back where we started again.”

This piece was originally published onMarch 8, 2011. This is a revised version.

Shine a Light for a Cause

Last year, Chris Del Bosco lit up Aspen en route to Winter X Games gold in Skier X. This year, he hopes to do the same for a country where snowfall makes world news, and whose last Winter Olympic team featured one cross-country skier.

Read more

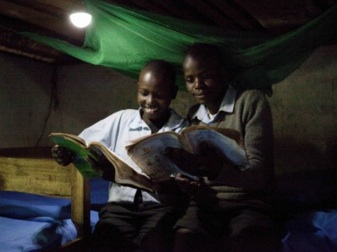

By partnering with the Denver-born company Nokero, who make the world’s only solar powered light bulb, Del Bosco has found not only a sponsor but also an ally in charity. Nokero—which is short for “No Kerosene,” as in the polluting substance often burnt for light by those without electricity—has teamed up with the defending Skier X gold medalist in a program called Ski 4 Light, where Del Bosco aims to raise $20,000 in donations and thus deliver 1,000 solar-powered bulbs to Kenya.

“I wanted to find something worthwhile,” said Del Bosco by phone as he drove to Aspen on Wednesday for ESPN Winter X Games 15, which run from January 27-30. “And this was a perfect fit for me, I was looking for something to add a little bit of meaning to my skiing.”

In addition to donations, Del Bosco and Nokero have pledged an additional 1,000 bulbs if he can successfully defend his title. And as if to remind the world of their project, Del Bosco’s helmet will feature a solar panel and battery powered-LED with the word “Nokero” emblazoned across the front, he says, “like a sticker.” Del Bosco will also travel to Kenya in July to bring the bulbs as part of the Bold Leaders exchange program, where American children visit Kenya while Kenyans come to explore the outdoors in the US in an effort to improve relations between the two countries—one bountifully electrified and the other were many still use kerosene lamps.

“We never really think about it,” said Del Bosco. “We turn on a light switch and we have lights and a lot of these people live off the grid.”

Nokero’s solar-powered bulb inventor Stephen Katsaros, a friend of Del Bosco’s from back when they were both living in Vail, said that although the company was originally skeptical of the partnership, when the charity side came up, things began moving quickly.

“Chris is just a wonderful person, I think that we came up with this really sweet idea,” Katsaros said.

That idea (the helmet) was then hatched on the first day of the new year, four days later engineers began building the model and after two prototypes it’s ready—like Del Bosco—to go at X. Indeed, as if on top of Del Bosco’s long road to the sport—he was kicked off the US Alpine team at age 17 for a positive marijuana test and in 2006 made a last-chance qualifier to Winter X where he went on to win the bronze—Del Bosco also had surgery last May after the Vancouver Winter Olympics on a 35% tear in the patella tendon of his left knee. He considered scrapping this season entirely, but after a strong rehabilitation in the fall currently sits at second in the World Cup standings and is ready for the main event in Aspen.

“It’s a big one, one I always look forward to racing,” he said. “This year I stepped it up and hopefully it’ll carry on through.”

Added Katsaros, “he went down the wrong path at one point, but he is where he is today because of hard work and stick-to-it-ness. He’s a great guy and he’s determined. He works so hard, he embodies a lot of the traits that I respect.”

And, to emphasize the goal of Ski 4 Life, Katsaros notes that 1.6 billion people in the world live without electricity.

“How incomprehensible is that for the average Westerner?” he asks.

About as incomprehensible as a September snowstorm in Kenya.

To donate to Ski 4 Light, visit chrisdelbosco.com or nokero.com. Photos courtesy of nokero.com.

This piece was originally published on January 28, 2011. This is a revised version.

Racing Up Jackson Hole—It Is What It Sounds Like

Sometimes hindsight exists on the finish line. At the bottom of Jackson Hole’s tram line, at the end of the 2011 US Ski Mountaineering Championships, Mark Smiley looked at his wife.

“I knew when you started out,” he said, “it was like, ‘She’s having a good day.’”

Read more

Janelle Smiley gave a laugh that summed up the race. “It started out nice,” said the 29-year old from Crested Butte, “and got worse.”

Indeed, with a cloudy and warm morning at 6,000 feet morphing into a gale at 10,000 feet, Saturday’s field of 90 racers—divided into “race” (ultra-light setups for skinning and bootpacking up Jackson’s legendary pitches), “heavy metal” (backcountry gear running the race course), “recreation” (a separate course on any gear) and 2-person relay (the race course on any gear)—surely felt the spectrum of Teton winter weather. Still, considering last year’s race was in March, the colder, wilder weather and better snow were not the only changes brought on by the shift to January.

“It brought more people here,” said Pete Swenson, director of the US Ski Mountaineering Association. “We wanted to make it that if you’re national champion it’s the middle of the winter. It makes it more relevant.”

And international. Reiner Thoni, 26, who won the men’s race division on a course that features bootpacks up both the headwall above Jackson’s gondola as well as up Corbet’s couloir, hails from Belmont, British Columbia. He trains on logging roads in his native Canada but in between makes sure to get all the fresh snow he can.

“On your low-intensity days,” he said at the base after covering the 8,000 vertical-foot course—one that might as well be called Jackson’s Greatest Hits—in a blistering 2:39.14, “you gotta keep yourself happy.”

Brandon French, from Kalispell, MT, finished just behind Thoni in a time of 2:40.04.

“We had a pretty big group to start and it just slowly dwindled and then by the finish it dropped down to about five,” said the newly-crowned 30-year old US national champion (Thoni’s Canadian, recall). “The wind at the summit was the toughest part. It was just cold on the face, the fingers were frozen.”

In fact, with the wind chill at the summit well below zero, several competitors were advised to cover up bare skin against frostbite. That same wind also visibly wind-loaded the cornice above Corbet’s in slow motion, but it didn’t change Smiley’s take.

“Those bootpack couloir things were super fun,” she said “Totally into those.” Smiley finished in 3:07.21 with second-place racer Sari Anderson from Carbondale, CO coming in at 3:08.45.

“Sari and I were just tagging it back and forth,” she said. “I’d pass her and she’d pass me. Finally there at the end I guess I took it. She was awesome. I stuck on her tail and hoped I’d get second. The last little skin was kinda a kick in the pants.”

At the awards ceremony, with well-earned pizza and beer fueling the post-race, Swenson made it clear this event was essentially the big bang for the newborn USSMA, which sells licenses and provides race insurance for competitions around the country.

“And we’d like to bring back the national series and maybe invite some Canadians; go up there if they stop beating us,” he joked.

As for Saturday, however, where the top three American men and women automatically qualify to go to worlds, Swenson could already see the future.

"This is the most competitive race we’ve ever had in North America, and getting more people at the event, its really rewarding,” he said. “Yeah, it was pretty junky, everyone was totally blown over. But it was awesome too.”

This piece was originally published on January 10, 2011. This is a revised version.

The following three pieces were written for and published by The U.S. Ski Team.

Picking the Races, With a Racer

What do Lindsey Vonn and Albert Pujols have in common? Aside from reaching the pinnacle of their respective sports thrice—Pujols as a World Series competitor, Vonn as the Audi FIS Alpine World Cup overall champ—not much. That is, until you factor in fantasy baseball and FantasySkiRacer.com, where both are perennial #1 picks.

Read more

Still, this wouldn't be so without Steven Nyman, an alpine World Cup winner and longtime participant in Fantasy sports, whose desire to create more excitement for ski racing fans has found its perfect counterpart in the growing online fantasy sports community. The result: FantasySkiRacer.com, where you pick the races.

"I want to connect the fans with the racers," said Nyman. "And have them learn more about each race and learn more about each track."

Nyman hatched FantasySkiRacer.com with his brother Michael and teammate Nolan Kasper in November 2010 and, with the help of friend Pete Rugh of RughsterDesign.com, assembled the website where fans (and racers) now compete virtually on the World Cup circuit. Players pick the top 10 finishers of each race and are awarded points based on how accurately a player predicts their racers' outcomes. And though picks like Vonn, Mancuso, Miller, and Ligety are commonplace, picking a teammate like 16-year old Mikaela Shiffrin, who notched her first World Cup top-10 in November and then her first podium in December, speaks to the educational side of FSR.

"Mikaela's been good for me this year," said Nyman. "I had her in third when she got her first podium…And each track is different, and you can move your picks according to each track. You have to learn what the conditions are."

At the end of the season, the top three places overall win a Fischer ski package, a POC helmet and goggle package, and a Dragon Wax ski package, while the winner of each weekend takes home SkullCandy headphones. Nyman is also quick to note that you can join at any point, since your score is calculated as a points average of your picks. And he's beginning a "Mega-League" for USSA members only, one that starts with World Cup Finals in Schladming, Austria of this year and will feature a $500 giveaway each weekend, beginning in Austria, that will continue into next season.

"The main thing we want to do is educate people on ski racing and integrate them more with the ski industry," he said. "In any athletics these days, there's a huge separation between the athletes and the fans…I think this is a good way to connect with the fans. We want to create that camaraderie with people following their favorite ski racers. Hopefully it'll grow the fan base. Hopefully they learn more about the sport."

FantasySkiRacer already has 4,000 users, 90 percent of whom hail from North America.

"We want to have it so you can do a lot of research and follow them more, not just from America but from all over the world. Ski racing is big in Europe so I think the game could take off over there. We want to make it a world-wide game."

Teammate Colby Granstrom is currently the overall leader, and there's an unwritten law among U.S. Ski Teamers requiring you to pick yourself. As Nyman says:

"If you're racing and you're not picking yourself to win, you shouldn't be racing."

To start making your picks, sign up at FantasySkiRacer.com and sharpen your edges. USSA Members can send their user name and member number to fantasyskiracer@gmail.com to join the USSA Mega-League.

This piece was originally published on February 29, 2012. This is a revised version.

Landon Gardner Helps Killington Rebuild

Read more

It was March 25, 2007, and—down to his last dual moguls run at the Sprint U.S. Freestyle Championships hosted by Killington—freestyle moguls athlete Landon Gardner had all his teeth intact. Fast forward to August 28, 2011, when those in Killington and the surrounding area had all their homes, utilities and lives in tact. Within a matter of hours, however, the two would need each other in ways they never could've foreseen.

Upon landing the first air of his last run, Gardner's knee violently met his chin, splitting it open and chipping several of his teeth. Gardner still went on to finish his run, but required stitches for his chin and a dentist for his teeth. After sewing him up, a Killington clinic made a phone call to a couple in nearby Rutland, VT, who in a matter of hours had him back at the mountain, albeit bandaged, but on his way to recovery.

Over four years later, on Aug. 29, Hurricane Irene made landfall in New England, tearing through Vermont and flooding the state. Killington's K-1 base lodge was partially destroyed along with roads and homes in the Route 4 area, and 12,000 people were left without power.

It was in the wake of such devastation that Gardner channeled his inner dentist, so to speak. From September 22-28, Gardner set up ten eBay auctions, selling items such as goggles, bindings, and, notably, a bib from when Killington hosted the National Championships in 2007, with all the proceeds going to Killington Community Relief (KCR).

"It's one of the first times that I've done something like this, and I do have some really fond memories of that place," he said. "There's more than just you and the mountain, there's community, resorts and people."

In reaching out to KCR, Gardner was looking to target precisely those people who live in the Killington area and were in need post-Irene.

"They told a pretty compelling story about families who were displaced and schoolchildren who were living with other families," said Gardner. "And I knew right then that any amount of money I could raise would go to a good cause. That's one of the reasons it stuck with me, it's a little closer to the individuals."

This piece was originally published on October 31, 2011. This is a revised version.

Athlete Spotlight: Emily Cook

Five-time U.S. champion and ex-gymnast Emily Cook grew up in suburban Boston and never let go of a dream to compete in the Olympics. Two Olympic Games and six World Championships later, she is the dominant force in women's aerials. Read on to see what makes Emily tick.